Telling the Truth (with Auggie Wren's Christmas)

Monday, December 19, 2016 at 02:54PM

Monday, December 19, 2016 at 02:54PM

"The fiction writer’s task is not only to invite the reader into the world of fiction, but also to permit the reader, once he has entered, to believe in its reality; the writer’s task is to create the illusion of truth, a story to believe."

From: The Reader at Play in "Auggie Wren's Christmas Story" by Paul Auster.

I don't know of many really great Christmas stories – for sure Dickens comes to mind, and even more so, the brilliant performances of Alastair Sim and George C. Scott in that famous role. And then there is my family tradition of reading Leacock's Hoodoo McFiggin (best sad/funny Xmas story of all time). For me, to complete the trilogy of awesomeness, it has to be Auster's Auggie Wren story.

To wind it back a bit...

Even though the idea of becoming a writer was in the vestiges of my brain ever since I was a kid, there were three moments that I can remember, quite clearly, that told me... okay, I need to write.

Moment one was reading Marquez's Hundred Years of Solitude. I'll write about that in another post some time, but it was life changing. Moment two came around the same time - in my early 20s - when I finally read Catcher in the Rye for the first time. Also life changing, and somehow bringing me closer to the idea that I could write something, or better, I needed to write something. But I was busy drawing and painting stuff as an illustrator, and deeply involved in that passion (and my sole source of income for a couple of decades.)

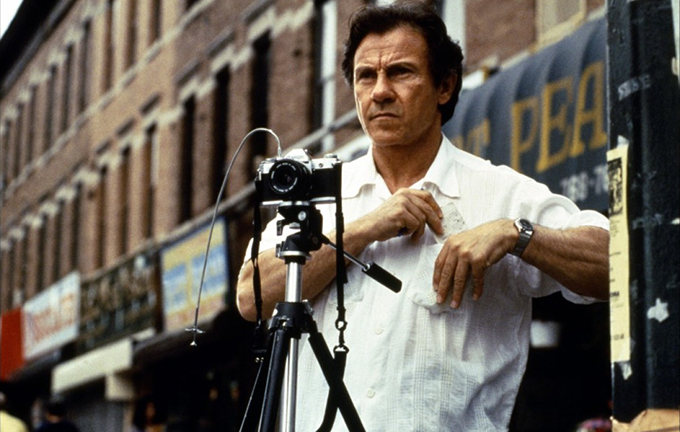

Moment three was unexpected. And it came in 1995, when I was 32 (did some quick math there). I went to a movie by myself, a smaller independent film, starring Harey Keitel and William Hurt. the moive was called, Smoke. And it was written by Paul Auster, directed by Wayne Wang. It was much later that I discovered the original Auggie Wren story from which Smoke emerged (Wren played by Keitel). But the particulars don't matter. What did matter was that exact moment when I walked out of the theatre, my head filled with one thought, "OK, enough fucking around. You need to write."

That was a while ago (I'm not doing the math), but I still recall that it was the storytelling that nailed me. Jump some years later when I disappear into Raymond Carver, and then Richard Ford, and re-visit Hemingway, and read more Marquez, and, and, and... the world of story somehow just opened for me. As much as I loved sci-fi, fantasy, and all sorts of genres, the ones that always got me were the "real stories."

Now, Richard Ford would haul off and smack me one if I even uttered the phrase "dirty realism" – and rightfully so. Because good fiction isn't real, it only seems that way. John Gardner's Art of Fiction talks about the fictional dream, and many writers will tell you how they are in the business of lying. But it is in lying well, and making the fake become real (in fact, you don't want the fake at all!) In a word as simple and complex and profound, and yes, pretentious, great fiction seeks the truth. It's Hemingway's "one true sentence" played out in its largest form.

If you're familiar with either the movie Smoke, or the Auggie Wren story Auster did for the New York Times, then you know how it is a story within a story. Incidentally, I found out they made this story into a short book, complete with illustrations. That kind of shit really burns me. When publishers take a thing that is beautifully short, and just fine in its own form, and put it between some hard covers (make the type extra big, so you don't figure out how little you're getting), and maybe a few drawings or photos to plump it up. The worst is when they take Vonnegut's or Elmore Leonard's writing rules, and because they know us writers are desperate for any craft words from the masters, they slap a fat price tag on it, and we can't buy it fast enough. Or else a well meaning friend gifts it to us. Uh, yeah, I liked it the first 300 times I read it on the internet. Nice font though.

I digress. Or rant. It's hard to tell sometimes.

And no, I am not linking to any of those books.

In the story, the main character (writer Paul Auster, as himself), talks with his friend the cigar store owner Auggie Wren (who I always think of as Harvey Keitel because I saw the movie before I read the story) about being commissioned by the New York Times to write a Christmas story. Auggie says this:

"A Christmas story?" he said after I had finished. "Is that all? If you buy me lunch, my friend, I'll tell you the best Christmas story you ever heard. And I guarantee that every word of it is true."

It's the every word of it is true that gets me. Because without realizing it we all lean in, just the like the fictional writer does. Why? Because we are about to be told something that is true. A true story. Who doesn't love that? Now, it is important to say that Auster's superb craft in everything leading up to this point, and everything after, is what convinces us of the truth in this story. It is in there right from the beginning of the story:

I heard this story from Auggie Wren. Since Auggie doesn't come off too well in it, at least not as well as he'd like to, he's asked me not to use his real name. Other than that, the whole business about the lost wallet and the blind woman and the Christmas dinner is just as he told it to me.

If you want to disappear into literature geekdom, follow the link to essay above, where the writer expounds on the idea of "storylistening". For me, this is at the heart of what I try to do with my stories - I am trying to make something real. Yeah, yeah, "true' - but even writing that out seems so damn inflated.

One of my favourite instances of this is at the beginning of Twain's Huckleberry Finn:

You don’t know about me, without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain’t no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.

So that sums up all you need to do in your writing: tell the truth. Easy-peasy lemon squeezey.

Here's a link to the full text of Auggie Wren's Christmas Story by Paul Auster – read it to your family this Christmas eve.

And here is that amazing clip from Smoke, where Auggie tells his story. Enjoy. (Also great Xmas viewing)

Reader Comments